This tutorial focuses on user administration on Linux hosts, managing users and groups.

As a system administrator, you are manipulating users and groups all the time.

You may be required to create a new user account for a new member in your team for example.

You may also be asked to create specific accounts for databases or for special tools you install on your host.

If your host grows, you may be also tempted to create groups in order to have a clearer understanding of the rights your assign to your system members.

As a consequence, having a perfect understanding of user administration is a very core skill for experienced administrators to master.

In today’s tutorial, we are having a very close look at user administration : how to create users, delete them but also how to setup a clear password policy on your system.

You are going to discover all the commands associated with user administration as well as the specific files that you need to look closely.

Ready?

What You Will Learn

By reading this tutorial until the end, you are going to learn about the following subjects.

- What user accounts are on Linux and how they differ from each other;

- What are groups on Linux and what the different group types are;

- How to create, delete and modify existing users on a Linux host;

- What are the passwd and shadow files on your system and what information they contain;

- How you can configure password aging with the chage command;

- How you can grant users with privileged rights via visudo and usermod;

As usual, that’s quite a long program, so without further ado, let’s have a look at what user accounts are on Linux.

User Administration Basics on Linux

If you are running your Linux system, it is most probably running as a multi-user system.

It means that multiple users are allowed to connect to the same host in order to share resources or to perform different operations on the system.

However, as you may have noticed already, not all user accounts are the same.

Some may have more permissions than others. On the other hand, some may be more restricted than others, not being able to launch even a simple shell process.

User Accounts Types

On Linux, you will have to deal with three different types of user accounts :

- Root account : which is by definition the most powerful user account of your system. The root user can perform any operation (like changing passwords for example), it can kill any processes and it can navigate to any directories on the filesystem.

- System accounts : system accounts are accounts used by processes or programs on your host. You may have seen that specific accounts are used for mail administration, or to run a simple Apache server. Those accounts are often given restricted permissions and they are prevented from accessing an interactive shell.

It is recommended not to modify those accounts by yourself.

- User accounts : user accounts are accounts used by real users. They may be members of your team or accounts that you created in order for them to retrieve some files on the host. Contraty to system accounts, it is very recommended to modify those accounts in order to give them a correct configuration.

Those accounts are most of the time given interactive shells (like bash or sh) in order to run commands on the system.

Note : on some hosts, it may be recommended to lock the root account in order to avoid any security issues.

User Accounts Identifiers

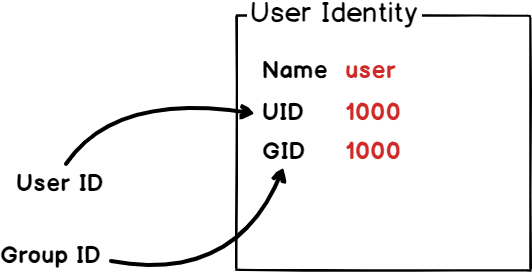

On Linux, accounts are identifier by a user ID, also called UID.

This is very close to the concept of PID for processes, UIDs are used in order to uniquely identify users on a system.

Moreover, they are often used in order to categorize user accounts on a Linux system.

As we already discussed, user accounts are split into three categories. As a consequence, UID are also assigned to users depending on the category they belong to.

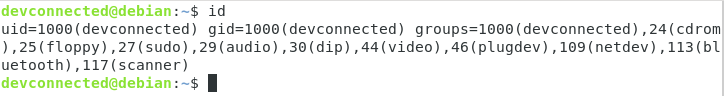

To see the information related to your ID, run the following command

$ id

As you can see, my own personal UID is 1000.

But why isn’it zero, or one?

On Linux, user IDs are assigned given the following rule :

- The root account is given the UID 0, as well as the GID 0.

- System accounts, the one created by the programs you use on your system, are assigned a custom range that can be either 1 to 500 or 1 to 999. On Debian based systems, the range for system accounts is from 1 to 999.

- User accounts are given UIDs greater than 1000. This is what you actually saw on the picture shown above.

Customizing user identifiers

On special cases, you may be tempted to customize the way UID and GID are assigned on a Linux system.

Sometimes, users are defined locally on the system, but they may also be defined in an external user administration system like LDAP for example.

As a consequence, if LDAP keeps UID from 1000 to 9999, you may want to assign local user an UID greater than 10000 by default.

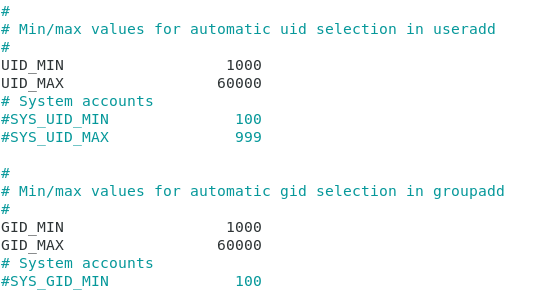

Customizing user identifiers is done in a file named login.defs on your host (located in etc)

To have a look at default identifiers given on your host, take a look at the login.defs file and find the following section.

$ nano /etc/login.defs

Groups and Group Types on Linux

By default, users on your host are assigned one or multiple groups.

On Linux, groups are created in order to have users sharing the same set of permissions or the same restrictions on a Linux host.

By default, when you create a user account, a group having the same name is created with it. As a consequence, every user belongs to at least one group.

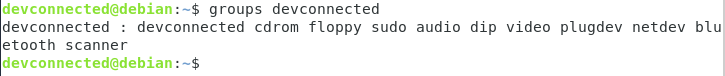

To illustrate it, run the following command on your system

$ groups <user>

By default, groups are split into two categories on Linux :

- Primary group : one user may have one (and only one) primary group at a time. A primary group is the group assigned when the user creates a file or a directory on the system. As a consequence, you may be tempted to modify a user primary group in order to tweak its default file creation group.

- Secondary groups : users may belong to many other groups. If they belong to a specific team on your host, they will belong to this group (administrators for example). As a second example, privileged users may belong to the sudo group (on Debian) or to the wheel group (on Red Hat based dstributions)

Groups are also given specific identifiers in order to differentiate one from another on the system.

They are called GID and they can also be modified by inspecting the login.defs file on your filesystem.

Now that you have a clearer understanding of what users and groups are on Linux, let’s see what commands you can execute in order to add or to remove users on your system.

User Administration Commands on Linux

On your system, you may choose to add, remove or modify local accounts.

Warning : you will need to have sudo privileges on your host in order to run those commands or to connect as root.

Here’s one guide for Debian based systems and one for Red Hat based systems.

Creating user local accounts

In order to create user local accounts on Linux, you have to use the useradd command.

$ useradd <user>By default, unless you modify configuration files, the command will create a home directory for your user as well as preset files like .bashrc, .profile and .bash_logout.

However, the useradd command exposes may different options to tweak user account creation :

- -d : for home directory. By default, accounts will be created in /home but you may choose to have a different path on your filesystem;

- -e : expire date. Useful when you are creating accounts for external consultants that are to leave on a specific date;

- -g : for GID, this option is set to have a custom GID for the user when creating the account;

- -G : for supplementary groups, this option is set to have secondary groups assigned to the user by default;

- -M : for no-home, this option is used to prevent the system from creating a home directory for the user;

- -r : in order to create a system account for the user;

- -s : for shell, this option is used to customize the shell assigned to the user by default (/bin/bash, /bin/nologin, /bin/false, /bin/sh and so on)

- -u : for UID, similarly to the -g option, this is used in order to customize the default UID assigned to the user.

As an example, you can create a standard user account on system.

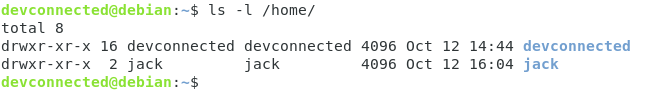

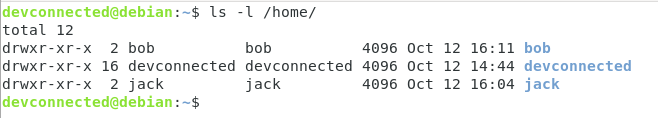

$ useradd johnYou can then have a look at the home directory to check if one entry was created for the user.

As you can see, no home directory was created by default for the user.

To address this issue, let’s specify the correct option and try again.

$ useradd -m bob

Now that your user is created, you will have to assign a password to it, otherwise it won’t be accessible.

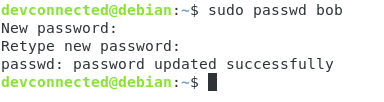

Changing a user password on Linux

To change a user password on Linux, you have to use the passwd with elevated privileges.

$ sudo passwd <user>If we take the example of the account we created earlier, we would run the following command.

$ sudo passwd bob

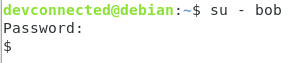

Now that the user password is set, you can quickly connect to the user account with the su command.

$ su - <user>

As you can see, the shell given to the user by default is quite special.

It is not a regular bash shell, in fact it was assigned a complete different shell called the dash shell (/bin/sh).

Why?

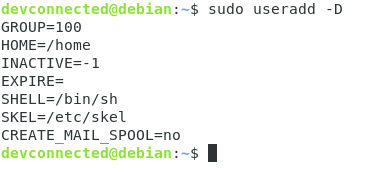

By default, useradd uses a default set of options that are entirely customizable on your host.

Changing useradd defaults on Linux

In order to check the different default options for the useradd command, run the following command

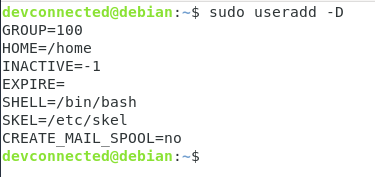

$ useradd -D

You may also find the same content in the /etc/default/useradd file on your system.

As you can see, the default shell is set to /bin/sh by default.

This is exactly why the new user had this shell defined by default.

To modify defaults, you should not directly the default file on your system.

If you make any errors in the process, you would take the risk of not being able to run your useradd command again.

For example, to change the default shell used, you would have to run

$ useradd -Ds /bin/bash

User Home Directory Skeleton

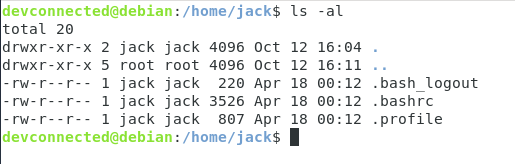

If you chose to create a home directory for your user, you may have noticed that some files are available into it by default.

Where are those files coming from?

When creating a home directory, your Linux system will copy files from a directory called “skel” on your system that is located in /etc.

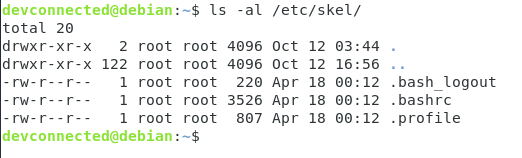

If you were to take a look at files located in /etc/skel, you would the exact same files as in a default home directory

$ ls -al /etc/skel

As you probably guessed, adding some files to this skel directory will add the files to default home directories on your host. It can be particularly useful when you need to add README files if you have custom rules on your server.

Removing a local user account on Linux

In order to remove a user account on your system, you have to use the following command

$ userdel <user>However, there is one important rule that you need to know about userdel.

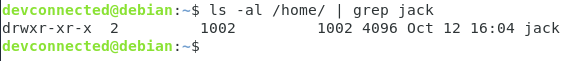

The userdel command will not delete the home directory as well as the files owned by the user on the system by default.

If files or directories are still present on the system with no user, they will be marked with the user previous UID and GID.

To delete a home directory with the user, you have to use the -r option.

$ userdel -r <user>This will not delete files located outside of the home directory.

To find files located outside of the home directory, you would run the following command.

$ find <path> -uid <uid> Looking to find and locate files on Linux easily, read the guide!

Modifying an existing user account on Linux

In some cases, you may want to modify an existing user account on your system.

To modify a user, you have to run the usermod command

$ usermod <option> <user>With usermod, you have many different options :

- -c : for comment, this command is used in order to modify a comment associated with a user in the passwd file;

- -d : home directory, used to modify the default home directory for the user;

- -g : used to modify the primary user group;

- -a : for append, this is used to assign secondary groups to a user by appending it to the existing list of groups for the user

- -G : used to assign secondary groups to a user (for example a sudo or wheel group);

- -L : used in order to lock the user account;

- -U : used to unlock a user account

For example, if you want to add a user to the sudo group, you would run

$ sudo usermod -aG sudo <user>Now that you have a clearer understanding of the commands you can run to add or delete users, let’s see some important files related to user administration.

Passwd and shadow files

On Linux, there are two main files that are related to user administration : the /etc/passwd file and the /etc/shadow file.

Understanding the passwd file

By default, the passwd file shows a list of all users available locally on your Linux system.

To have this listing, run the following command

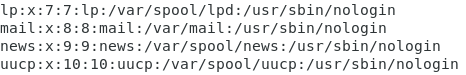

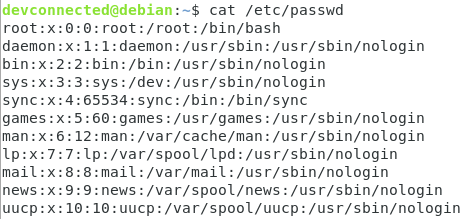

$ cat /etc/passwd

As you can see, the passwd file is a colon separated file having multiple entries, one for each user available on your system.

From left to right, the columns display the following information :

- Username : the actual username for the user on the system;

- Password : having a “x” entry simply means that the password is available in the shadow file in an encrypted format;

- UID : the unique user ID we described earlier;

- GID : the ID for the primary group for the user (that may differ if you customized it);

- Comment : a descriptive comment that might be helpful in order to identify the user, this field is also called a GECOS field;

- Home directory : if the user was assigned a home directory, or a custom field, this is where the information is stored;

- Default shell : the shell assigned to the user when creating it.

If you were to create a new user with the useradd command, a new entry would automatically be added to this file.

On the other hand, the shadow file contain more sensitive information about your system.

Understanding the shadow file

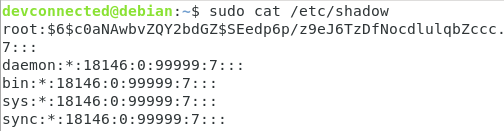

To have a listing of the shadow file, make sure you are running the command as a privileged user

$ sudo cat /etc/shadow

By default, the shadow file showcases the following columns :

- Username : the actual username for the user on the system;

- Password : this is where the encrypted password will be stored. By default, you can find information about the encryption system by inspecting the first three characters (in this case, $6$ is a SHA-512 encryption);

- Last time the password was changed : number of days since 1 Jan 1970 until the most recent modification of the password. In this case, 18146 days gives the 7th of September 2019;

- Minimum number of days between password changes : meaning the number of days before a user is allowed to change its password;

- Maximum number of days for a valid password : the maximum validity period for a password on the system;

- Warning period : this option defines the number of days before a password expiration for the user to receive a warning message about its account;

- Inactive period : when your password expires, it defines the period before the account is disabled;

- Expiration date : defines the number of days since the 1st January 1980 before the account is disabled.

Note : a “!” or a “*” in the password means that the user login is disabled on the system, as you are probably dealing with a system account.

Now that you have a clearer understand of the passwd and of the shadow file, let’s see how you can manage password aging with commands.

Managing password aging with chage

On Linux, the way to modify all the parameters we have seen before is to use the chage command.

$ chage <options> <user>Where options are the following ones :

- -d : for last day, this option sets the number of days since the password was changed for the user account;

- -E : for expiration : sets a date of a number (since 1st January 1970) on which the user account will no longer be accessible;

- -I : for inactive, this option sets the number of inactivity days before the user account is disabled on the system;

- -m : for min days, sets the number of days before two consecutive password changes. If you set this value to zero, it means that the user is allowed its password at any time;

- -M : for max days, this option sets the maximum validity of a password on the system. This is one of the options that you have to carefully configure if you set a good password policy on your hosts. Also, if you compute the last password change with the max days option, you will find the day when the user has to change its password;

- -W : for warn days : sets the number of days before password expiration on which the user account will be given a warning for password expiration.

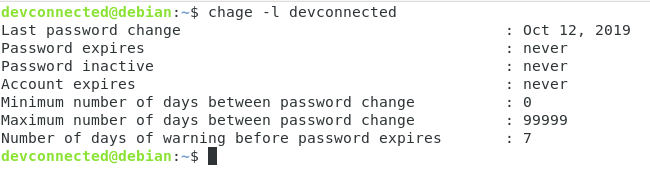

In order to have a complete listing of the active password policies for your account, you have to run the following command

$ chage -l <user>

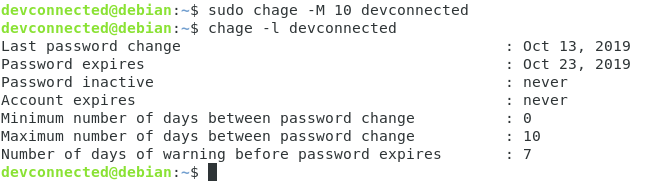

As you can see here, I am given all entries relative to the options specified before.

In this case, I changed my password on the 12th of October 2019, and I will never be forced to change my password ever again. However, those options can be easily changed.

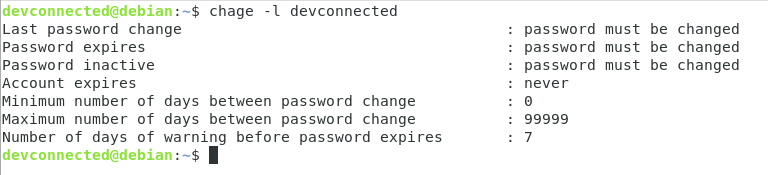

Forcing password change

In order to set an immediate password change for a user on the host, you have to run the following command

$ chage -d 0 <user>

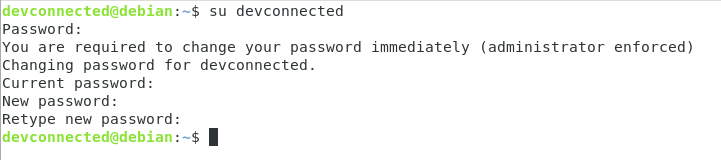

As you can see here, the user password will have to be changed on the next login.

Try to login as the user in order to see that you are prompted to change your password.

$ su <user>

When changing your password, you will be able to access your user account as before.

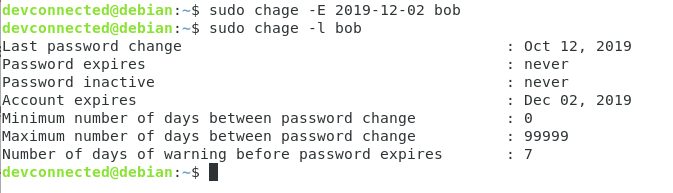

Setting an account expiration date easily

As described before, you may be able to change the account expiration date with the -E option.

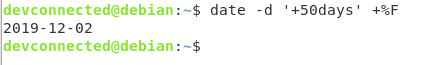

However, it may be hard to guess the date twenty, thirty of eighty days from now.

In order to set the expiration date for an account fifty days from now, type the following command

$ date -d '+50days' +%F

From there, you can easily set the expiration date on this account.

$ chage -E <date> <user>

Setting password expiration for a user

In order to set a password expiration for a user, you have to modify the maximum number of days until it has to change its password.

For that, you have to use the -M option.

$ chage -M <days> <user>As a consequence, the password expiration date will be set when executing the chage command.

Locking and unlocking a user account

In some days, password expiration is simply not enough.

For security reasons, you might want to expire (or lock) a user account completely. This can be used in order to prevent a user from accessing your hosts when it should not be able to do so.

In order to lock a user account, you have to use the usermod command.

$ usermod -L <user>As a consequence, the user won’t be able to connect to the user account.

To unlock it, you can use the usermod command with the -U option.

Granting privileged rights to users

On Linux, you essentially have two ways to set privileged, i.e sudo, rights to user accounts.

You can either use the usermod command to add users to either the sudo group (on Debian based) or to the wheel group (on Red Hat based).

To quickly add a user to sudoers, run the following command

$ sudo usermod -aG sudo <user>Or on Red Hat

$ sudo usermod -aG wheel <user>You can also directly modify the sudoers file with the visudo command.

We already explained those steps in the following articles :

Conclusion

In today’s tutorial, you learnt more about user administration essentials on Linux.

You learnt that you can add, delete and modify users and you can also tweak the password policy in order to ensure that you do not leave security holes on your system.

You also have seen that you can read specific files on the filesystem in order to have complete information about users and groups.

If you are looking to list users on Linux, you can read the following guide.

Also, if you are curious about Linux System Administration, you should check all the guides we already published in this section.

3 comments

“having a perfect understanding of user administration”

Who defines what is a “perfect understanding”?

“User accounts are given UIDs greater than 1000. This is what you actually saw on the picture shown above.”

In the picture above the UID was 1000. 1000 is NOT greater than 1000.

If using the useradd command, then on Debian + Debian derived systems, the first user id starts at the value of

FIRST_UID in the /etc/adduser.conf configuration file.

re usermod -L — “As a consequence, the user won’t be able to connect to the user account.”

Not true if the user has remote access with ssh using a trusted keys with the setup an authorized keys file in the user’s ~/.ssh directory.

Thank you for the clarification and details provided!

[…] explained in other tutorials (about user administration), you can get the current user ID by using the “id” […]